Diepsloot has some of the highest rates of violence against women ever recorded in South Africa: they are more than double those reported in national studies.

The Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism ran an SMS-based help line for victims of gender-based violence in Diepsloot between December 2016 and July 2018. We sent out 2,628 SMSes to callers to the helpline telling them where they could get help in Diepsloot. Take a look at the data we collected.

In October 2013 the bodies of two little girls, one three years old, the other, her two-year-old cousin, were found in a broken public toilet near their home in Diepsloot, a township in northern Johannesburg. The Mail & Guardian’s Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism visited the family in 2015 and reported on the disturbing prevalence of rape in the community.

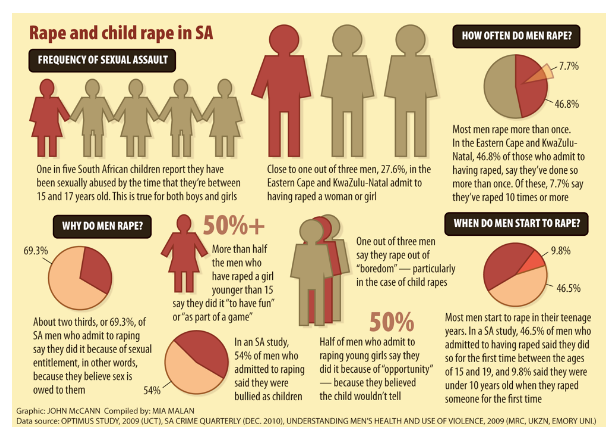

Then in early 2016 Sonke Gender Justice, a non-governmental organisation, and the University of the Witwatersrand, as part of a research project looking into gender violencea in Diepsloot, interviewed 2,600 men, aged 18 to 40 years, living in the community. They found that rape and physical abuse rates are more than double those reported in national studies.

More than half (56%) of the men in the study said they had used physical or sexual violence against women. In national studies 14% of men reported enacting violence towards women.

Diepsloot has a network of NGOs and community organisations that offer support to victims of violence. Bhekisisa decided to set up a helpline/data project to try to help both the victims and the service providers in Diepsloot.

The helpline was named Vimba by Brown Lekekela, who runs the Green Door place of safety, one of five community partners in the project. "We named it Vimba because in Diepsloot when someone shouts 'Vimba!', we know that person needs help, and everyone will come out to help them," he said.

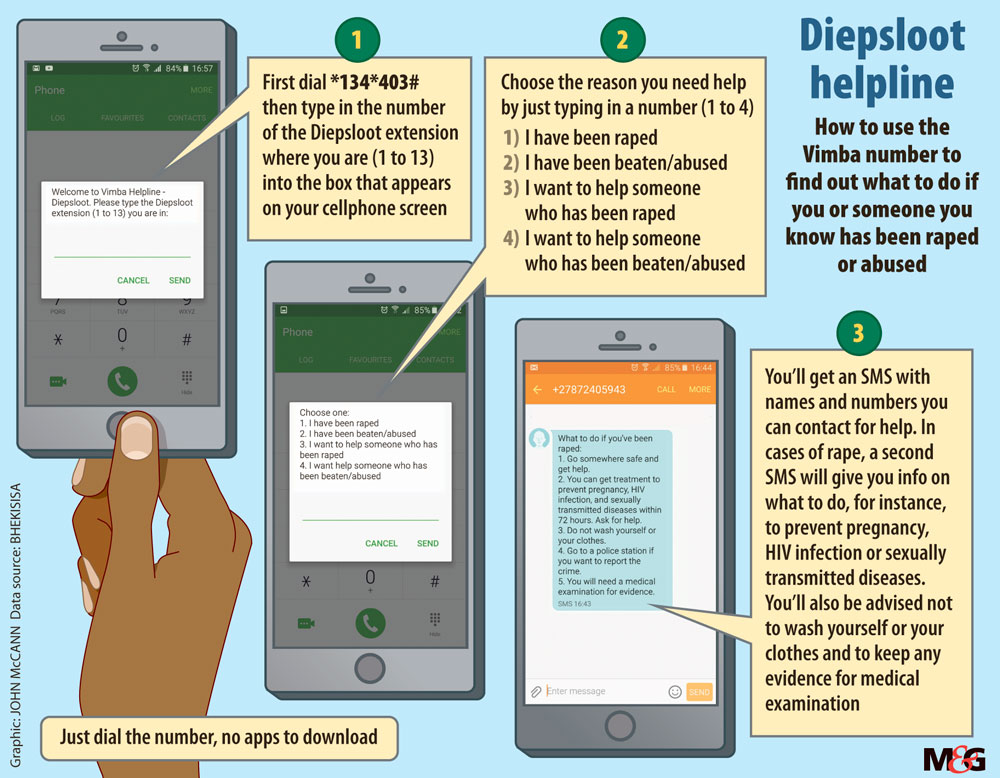

The Vimba Helpline has two functions. The first is to make it is easier for women and children who are victims of violence and abuse in Diepsloot to access the services and support available there. The second is to collect information about violence against women and children in the community that could be useful to the service providers.

It is a free cellphone-based service that uses USSD technology, which makes it possible for people to use the helpline even if they don’t have data or airtime. It also doesn’t matter what kind of cellphone they have, the service works on even the most basic phone.

Cellphones are widespread in Diepsloot, 90% of households have access to one, but only about one in four households have access to the internet. Up to half the working age population is jobless, a social audit by Sonke Gender Justice found. And those who do work don’t make very much money. As a result, data is a luxury.

Vimba has been set up so that all you need is a cellphone with a charged battery. People who dial the number are asked a series of questions about where they are and the type of help they need. They can chose one of three languages: English, Sepedi or Zulu. When they answer all the questions they are sent an SMS telling them where to go to get help in Diepsloot and phone numbers they can contact. If they indicate that they have been raped, they are also sent an SMS with information about what to. The calls and SMSes are reverse-billed.

At the back-end call data are collected by our USSD service provider and visualised in real-time on a dashboard which some of the project’s partners have access to.

Initially posters were made and put up in various public places around Diepsloot to publicise the Vimba helpline and make the *134*403# number easy to find. Now the message about gender violence and the helpline number is being painted on walls around the township.

Monthly data is downloaded from the USSD dashboard and analysed to make it easier to spot trends and patterns. Not all calls to the helpline are completed to the stage where the caller is sent an SMS. The completed calls are the ones that contain the most valuable data and those are visualised in the charts below.

Sorting the calls by day of the week gives an idea of whether more people contact the helpline over weekends than on week days. Dividing each day into quarters – midnight to 6am, 6am to noon, noon to 6pm and 6pm to midnight – makes it easier to see whether more calls are made at night than during the day.

Visualising the number of calls made on each day of the month can help to indicate whether more violence occurs at the end of the month when people have been paid (and are likely to have money to buy alcohol), or during public holidays, for example. Peaks in the number of calls made on a particular date can indicate whether certain events, such as a big soccer match, or even weather conditions are linked to an increase in violence against women and children.

The helpline menus are designed to distinguish between callers who are themselves victims of violence, and callers who know a victim and want to find out how they can help. It also distinguishes between rape and other types of violence or abuse.

The number of calls made from each of Diepsloot’s 13 extensions are recorded on the map below. This could provide an indication that an area is a violence hotspot that deserves attention.

(Please note: The numbers for December 2016 are exceptionally high because of the helpline's launch and other publicity events.

Also, from March 2017 an option was included in the "Where are you?" menu for people who don't live in Diepsloot.)

In April 2017, five months after the Vimba helpline was launched, Bhekisisa spoke to a rape survivor who found help at one of our partner organisations in Diepsloot using the helpline. She is one of 29 people who have sought and received assistance for problems such as domestic violence, sexual assault and rape, as well as help obtaining a protection order against a former partner.

Read Bhekisisa's story about the impact of Vimba, written by Pontsho Pilane, below:

In Diepsloot, Bhekisisa's Vimba! app is helping rape survivors access life-saving care and treatment.

One Friday night in April, Bianca Jonkers, her boyfriend and his cousin visited a local tavern for a fun night out. Jonkers, who prefers not to use her real name, had just relocated from the Western Cape to live with her boyfriend in Diepsloot, a township in northern Johannesburg.

"I came here to start a new life," she explains. "We first lived in the Western Cape, but then my boyfriend got a job in Johannesburg and I wanted us to be together."

Round about 11pm, the 41-year-old decided to return home. She left her boyfriend and his cousin behind for the 2 km walk to their rented backroom.

But about halfway, Jonkers was stopped by a group of seven men. "Give us your phone and money," they shouted.

But she had neither. "All I had was eight rands in my back pocket."

Jonkers pauses. She nervously swivels her keys.

"I knew I was in trouble. They started dragging me into a ditch where people dump their rubbish, next to a stream of water."

Four of the seven men raped Jonkers. Repeatedly. One held a knife to her neck and threatened to kill her if she screamed for help. "I was scared, I would rather be alive than to be stabbed to death," she explains.

She looks out the window of the wendy house of a Diepsloot rape counsellor where she sits in the corner of a white, foldable chair. "So I laid there, waiting for them to finish."

Free number for help

The next day Jonkers' landlord came to her help. The landlord dialled *134*403# on her cellphone – she had heard about the number at her church. She didn't need any data or airtime to dial the number, because the app's developers cover the cost of the data through "unstructured supplementary service data" (USSD) technology.

After Jonkers had dialled the number, she received an SMS with the numbers and addresses of organisations that could help. That's how Jonkers ended up at Brown Lekekela's wendy house.

He runs The Green Door, the only place of shelter in Diepsloot for women and children who have been abused. Lekekela counsels gender-based violence victims and helps them report their cases to the police. The Green Door is located in Extension 6, in his backyard.

Lekekela counselled Jonkers, who was still visibly devastated. "Every time I closed my eyes I heard their [the rapists'] voices. I could feel and hear everything but I couldn't see their faces."

Jonkers would never have received counselling if it wasn't for *134*403#. "Most rape victims in Diepsloot don't know where to find help," explains Lekekela. "They just try and move on with their lives."

According to a 2017 study published in the South African Journal of Psychiatry, receiving support and care from others helps sexual violence survivors cope significantly better with their trauma. But poor "integration of mental health services" at post-rape services result in only a few survivors receiving adequate trauma counselling.

While five organisations – The Green Door, Sonke Gender Justice, Lawyers Against Abuse, Africa Tikkun and the South African Depression and Anxiety Group – provide counselling and legal services in Diepsloot to victims of gender-based violence, few residents know how and where to find them.

In partnership with these organisations, Bhekisisa created and launched the Vimba! app in December. It helps survivors, who are mostly women and children, to know what to do and where to go when they've been abused. In addition to SMS'ing the contact details of the organisations, the app also sends a list of do's and don'ts to users and collects data about the locations they dial from, as well as the time of reporting.

Lekekela named the app Vimba!, a well–known cry for help in South Africa. Vimba! means ‘to prevent, stop or halt' in isiZulu. "If someone in the street is robbed or hurt and they shout: ‘Vimba!' people will run towards them to help. That's why we've chosen this name," explains Lekekela.

He has jotted down 28 people in his register book who have come to his shelter as a direct result of Vimba! this year. The other venues are still in the process of calculating their numbers.

Vimba!'s data shows close to 500 people have dialled the helpline between December and April.

In a 2016 study conducted by Sonke Gender Justice and the University of the Witwatersrand, 56% of men who were surveyed in Diepsloot admitted to having raped or beaten a woman.

"People in Diepsloot don't have airtime to phone me, so they will get my address from the app and walk here," Lekekela says. "When they get here, I counsel them and help them to report their rapes."

'This is not the Western Cape'

After raping Jonkers, the group of men left – except for one, who stayed behind to continue.

"He was very tall and dark, and his left hand was wrapped in a white bandage," Jonkers remembers.

She wipes the tears off her face.

"I could hear my boyfriend's cousin shouting my name, but I couldn't do anything. I was terrified that if I did he would hurt me."

The man left her in the ditch. Following the sound of passing cars and chattering foot travellers, a bruised and barefoot Jonkers staggered back to the main road. Eventually, she found her boyfriend and his cousin.

Jonkers wanted her boyfriend to call the police so she could open a case. But he refused. "He said to me: ‘This is not the Western Cape, the police in Diepsloot won't help us.'"

There is only one police station in Diepsloot. It services 13 extensions, with a population that local organisations estimate at about half a million. The only official figures come from the 2011 South African census, which counted 138 000 people in the township. Residents and businesses in the township say the population of Diepsloot is grossly underestimated.

In October 2015, Bhekisisa published a story, Diepsloot: Where men think it's their right to rape about the prevalence of child rape in Diepsloot. Vimba! is the result of the overwhelming reaction to the story, which led to a partnership with organisations working with gender-based violence survivors in the township.

No rape kits in Diepsloot

Jonkers listened to her boyfriend; she didn't call the police on the night of her rape. Together, they walked back home where she washed herself and went to bed.

But the sleep she desperately needed was nowhere to be found.

Lekekela however convinced her to report her rape to the police the next day. A detective from the police station drove Jonkers to Olivedale Hospital in Randburg, which is about 20 km away from Diepsloot. She was swabbed and given the morning-after pill to prevent her from falling pregnant, as well as a month's dosage of antiretroviral drugs, or post-exposure prophylaxis, to reduce her chances of contracting HIV.

Lekekela says the two local clinics in Diepsloot don't stock rape kits. The nearest Thuthuzela Care Centre – a one-stop, government-run service offering rape care – is at Tembisa Hospital, about 30km away.

Jonkers has also had therapy with a professional trauma counsellor.

According to Lekekela many people in Diepsloot don't understand what gender-based violence is and why it is wrong. "People believe that it is okay for a husband to demand sex from his wife, and to beat her if she doesn't oblige," he says. "Before we address the issues of violence, we need to make sure people understand it first."

When Vimba! was launched, posters were put up in public places like the mall and community centres around Diepsloot. But Lekekela believes more needs to be done to let everyone know about the hotline. That's why he and a team of volunteers started to paint murals with the Vimba! message across the township this year.

The words "Dial *134*403# from any cellphone – for free/mahala" are painted on the white wall of Jabulani Supermarket in Extension 11. The shop, which is located on a busy street, is opposite a hair salon, and next to a small tavern. A vivid picture of a man interjecting another man raising his hand to a woman is captioned: "Men taking action against abuse".

Lekekela explains: "Each of the extensions will have two wall paintings. This will make Vimba! more visible and more people will know about it."

The bruises on Jonkers face are slowly fading away. She still has an open cut on her right foot. All the physical remnants of her rape will soon be gone, but the ordeal will stay with her for a long time to come.

She still gets nightmares. "I wish this didn't happen to me." The "new life" Jonkers came to find in Diepsloot started horrendously. She bows her head. "If Brown didn't help me I would have killed myself." - Pontsho Pilane

Diepsloot is a densely populated triangle of land wedged between William Nicol Drive and the N14 freeway in northern Johannesburg. It was established in 1995, and has grown rapidly over the course of two decades as people flocked to Johannesburg in search of work.

In 2011 the national census put the population at 180,000, but it’s generally believed that by 2016 at least 350,000 people and possibly as many as half a million lived there. It’s a ramshackle, dust-coated mixture of tin shacks and brick-and-mortar houses, intersected by narrow roads, few of which are tarred.

Unemployment rates are high. The provision of basic services such as water and electricity is limited and there are very few social and recreational facilities, Sonke’s social audit found. For example, there are only three community halls and one youth centre, which has Diepsloot's only library.

There is one park, which was last renovated in 2008, and there is no public swimming pool. There are, however, more than 200 shebeens and taverns.

Part of the Sonke CHANGE Trial is holding workshops with men in Diepsloot with the aim of changing their attitutudes towards women and violence, and in this way reducing the levels of rape and violence.

The Vimba Helpline Diepsloot is a project of the Mail & Guardian’s Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism in partnership with five non-governmental organisations that provide services and support to victims of gender-based violence in Diepsloot: Sonke Gender Justice, Green Door Place of Safety, Lawyers Against Abuse, Afrika Tikkun and the South African Depression and Anxiety Group. The project was made possible by funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

If you would like to find out more about Vimba email info@vimbadiepsloot.co.za

Sonke Gender Justice works across Africa to strengthen government, civil society and citizen capacity to promote gender equality, prevent domestic and sexual violence, and reduce the spread and impact of HIV and Aids.

Green Door is a temporary place of safety in Diepsloot, where victims of gender-based violence also receive counselling and help accessing services.

Lawyers against Abuse provides free legal services and psychosocial support to victims of gender-based violence, also working with local state actors and community members to ensure victims receive justice.

Afrika Tikkun provides social workers and support for children. It works with Childline, which helps abused children.

The South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG) offers free psychosocial support and counselling for victims of abuse, violence and rape.

Bhekisisa is the centre for health journalism at the Mail & Guardian newspaper. Bhekisisa has published stories about child rape and gender violence in Diepsloot since 2015. It launched the Vimba helpline as a way to help the Diepsloot community get access to the organisations that can assist victims of violence.

Photographs of murals by Peter Mokhunoana and Brown Lekekela. All other photographs by Delwyn Verasamy, ©Mail & Guardian